The term favela dates back to the late 1800s. At the time, soldiers were brought from the conflict against the settlers of Canudos, in the Eastern province of Bahia, to Rio de Janeiro and left with no place to live. When they served the army in Bahia, those soldiers had been familiar with Canudos' Favela Hill – a name referring to favela, a skin-irritating tree in the spurge family (Cnidoscolus quercifolius) indigenous to Bahia. When they settled on the Providência [Providence] hill in Rio de Janeiro, they nicknamed the place Favela hill."

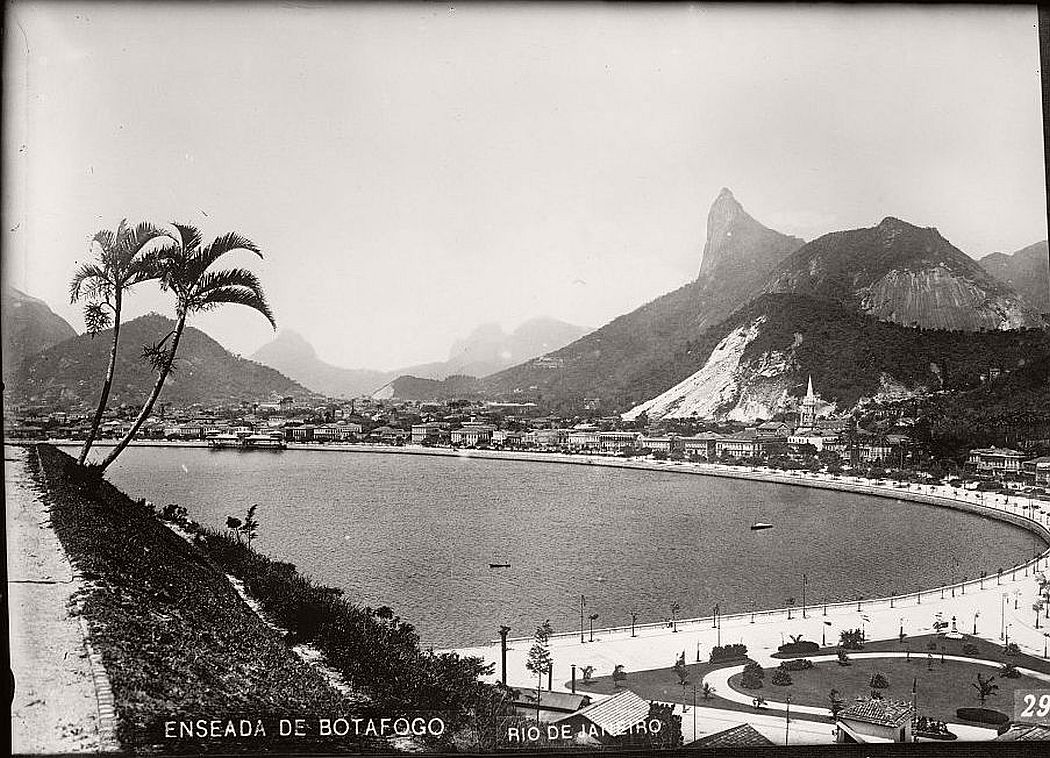

The favelas were formed prior to the dense occupation of cities and the domination of real estate interests. Following the end of slavery and increased urbanization into Latin America cities, a lot of people from the Brazilian countryside moved to Rio. These new migrants sought work in the city but with little to no money, they could not afford urban housing. In the 1920s the favelas grew to such an extent that they were perceived as a problem for the whole society. At the same time the term favela underwent a first institutionalization by becoming a local category for the settlements of the urban poor on hills. However, it was not until 1937 that the favela actually became central to public attention, when the Building Code (Código de Obras) first recognized their very existence in an official document and thus marked the beginning of explicit favela policies. The housing crisis of the 1940s forced the urban poor to erect hundreds of shantytowns in the suburbs, when favelas replaced tenements as the main type of residence for destitute Cariocas (residents of Rio). The explosive era of favela growth dates from the 1940s, when Getúlio Vargas's industrialization drive pulled hundreds of thousands of migrants into the former Federal District, to the 1970s, when shantytowns expanded beyond urban Rio and into the metropolitan periphery.

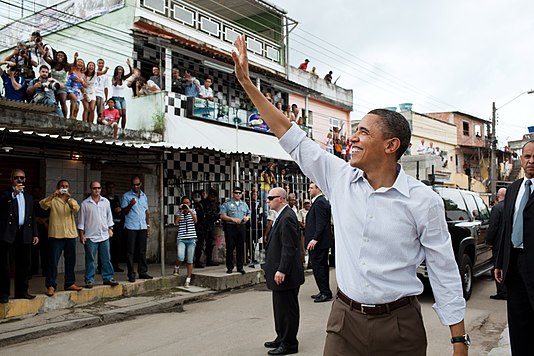

Former U.S. president Barack Obama visiting Rio's Cidade de Deus (City of God) favela. This favela started out as public housing built on marshy flatlands in the city's western suburbs.Urbanization in the 1950s provoked mass migration from the countryside to the cities throughout Brazil by those hoping to take advantage of the economic opportunities urban life provided. Those who moved to Rio de Janeiro, however, chose an inopportune time. The change of Brazil's capital from Rio to Brasília in 1960 marked a slow but steady decline for the former, as industry and employment options began to dry up. Unable to find work, and therefore unable to afford housing within the city limits, these new migrants remained in the favelas. Despite their proximity to urban Rio de Janeiro, the city did not extend sanitation, electricity, or other services to the favelas. They soon became associated with extreme poverty and were considered a headache to many citizens and politicians within Rio. In the 1970s, Brazil's military dictatorship pioneered a favela eradication policy, which forced the displacement of hundreds of thousands of residents. During Carlos Lacerda's administration, many were moved to public housing projects such as Cidade de Deus ("City of God"), later popularized in a wildly popular feature film of the same name. Poor public planning and insufficient investment by the government led to the disintegration of these projects into new favelas. By the 1980s, worries about eviction and eradication were beginning to give way to violence associated with the burgeoning drug trade. Changing routes of production and consumption meant that Rio de Janeiro found itself as a transit point for cocaine destined for Europe. Although drugs brought in money, they also accompanied the rise of the small arms trade and of gangs competing for dominance.

While there are Rio favelas which are still essentially ruled by drug traffickers or by organized crime groups called milícias (militias), all of the favelas in Rio's South Zone and key favelas in the North Zone are now managed by Pacifying Police Units, known as UPPs. While drug dealing, sporadic gun fights, and residual control from drug lords remain in certain areas, Rio's political leaders point out that the UPP is a new paradigm after decades without a government presence in these areas.

Most of the current favelas really expanded in the 1970s, as a construction boom in the more affluent districts of Rio de Janeiro initiated a rural exodus of workers from poorer states in Brazil. Since then, favelas have been created under different terms but with similar end results.

Communities form in favelas over time and often develop an array of social and religious organizations and forming associations to obtain such services as running water and electricity. Sometimes the residents manage to gain title to the land and then are able to improve their homes. Because of crowding, unsanitary conditions, poor nutrition and pollution, disease is rampant in the poorer favelas and infant mortality rates are high. In addition, favelas situated on hillsides are often at risk from flooding and landslides.